The Unrivaled Stench: Thioacetone and Its Infamous Reputation

Written on

Chapter 1: The Stench That Defies Belief

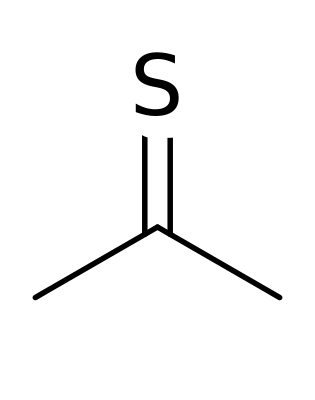

Thioacetone: A Compound That Laughs at Conventional Odor

“Today’s compound emits no sound and leaves no destruction. It simply stinks. Yet, its odor is relentless and unbearable, causing innocent bystanders to stagger, hold their stomachs, and flee in panic. Its stench is so potent that it leads people to suspect malevolent supernatural forces. This is thioacetone.”

— Dr. Derek Lowe, Science Journal

In his reflections, the philosopher-king Marcus Aurelius maintained his composure by recalling that the purple of his robes originated from dead shellfish—more specifically, marine snails. The city of Tyre perfected the art of harvesting this exquisite color, even though the process produced a scent that was far from regal. At least that endeavor yielded something unique—purple hues.

In stark contrast, thioacetone offers nothing beneficial. According to scientist Dr. Derek Lowe, its odor is beyond imagination. The compound itself seems to resist existence; it is inherently unstable and transforms into a polymer if temperatures exceed -20°C (-4°F). Problems arise when thioacetone lingers and someone attempts to open a container.

Dr. Lowe notes that pinpointing the source of the horrific smell is challenging because “when people start jumping out of windows and throwing up in trash bins… the quality of the data starts to decline.” While exaggeration is common, thioacetone has a reputation to uphold.

A Legacy of Odorous Infamy

A particularly notorious incident involving thioacetone dates back to an 1889 experiment in a laboratory in Freiberg, Germany. A reaction with this compound led to an odor that escaped the lab, resulting in evacuations and widespread illness throughout the city. According to Randall Munroe from the New York Times, the stench spread half a mile in all directions. Notably, this was not a large quantity of thioacetone—most accounts suggest it was closer to a beaker than a vat.

In 1890, Dr. Lewkowitsch, in The Chemical News, remarked that both thioacetone and rose oil share a peculiar trait: when diluted with air, their scents become more intense. While rose oil is delightful, thioacetone, in Dr. Lewkowitsch's words, becomes “fearful.” He recounted experiments where workers from the far end of the steelworks reported feeling too ill to continue their tasks.

Dr. Lowe also references experiments conducted in the 1960s at Esso Research Station in Abingdon, UK. During one incident, a bottle's stopper popped off, and even though it was replaced immediately, “an immediate complaint of nausea and sickness from colleagues working two hundred yards away” soon followed. Scientists discovered that minute amounts of thioacetone could be detected up to a quarter mile away “within seconds,” often without the researchers being aware.

Through experience, the team at Esso developed strict protocols for handling this substance to contain its foul odor:

“The offensive odors…are confined and eliminated by working in a large glove box with an alkaline permanganate seal, decontaminating all apparatus with alkaline permanganate, neutralizing obnoxious vapors with nitrous fumes generated by a few grams of Cu in HNO3, and destroying all residues by incinerating them in a brazier.”

By now, it should be clear: thioacetone is infamous for its odor. But can something so malodorous actually have utility?

Chapter 2: The Unexpected Uses of a Malodorous Compound

The first video presents a complete demonstration of making thioacetone, showcasing the process and the notorious smell associated with it.

The second video explores the creation of the stinkiest chemical known, examining its properties and potential applications.

Harnessing the Power of Odor

Randall Munroe points out that ethyl mercaptan is added to natural gas to impart a distinctive rotten egg smell. Without this addition, natural gas is odorless, making the stench a crucial safety feature for leak detection.

Conversely, David Hambling from The Guardian discusses a more sinister application: crowd control. He details the US Army's XM1063 project, which reportedly involves a shell fired from a howitzer that deploys various chemicals. One of the possible agents is a malodorant, or as Hambling describes it, “a super stink bomb.” A presentation from the US Army Field Artillery Center confirms this, stating:

“Artillery delivered malodorants will disperse crowds and separate combatants from noncombatants, thereby reducing civilian casualties at targeted locations.”

Hambling suggests this skirts the boundaries of the Chemical Weapons Convention, with some believing it crosses a line. However, consider the a