generate a new title here, between 50 to 60 characters long

Written on

Chapter 1: The Quest in the South Pacific Gyre

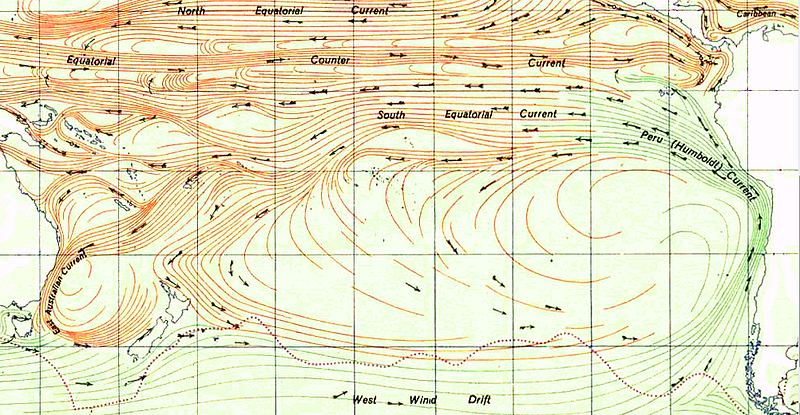

The search for microbial life in the South Pacific Gyre (SPG) has unveiled astonishing findings, including the discovery of ancient microbes that have potentially been dormant for over 100 million years. This remote region of the ocean is considered one of the most desolate places on Earth, located over a thousand miles from the nearest landmasses—Australia to the west and South America to the east.

The SPG is characterized by extremely low nutrient availability, with minimal dust and organic debris. In this deep oceanic environment, the term "marine snow" describes the organic remnants that drift down and settle as fine sediment on the seabed. This marine snow sustains the sparse and unusual creatures that inhabit these profound depths.

In this marine desert, marine snow accumulates at an astonishingly low rate—between 0.1 to 1 meter every million years. Yuki Morono, Ph.D., a senior researcher with the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC), led a team to explore what microbial life could persist under such challenging conditions.

Section 1.1: The Expedition Begins

In the fall of 2010, the research team set sail aboard the JOIDES Resolution drillship, embarking on a journey to drill in waters as deep as 19,000 feet. They retrieved samples of clay and marine snow that had accumulated over eons.

The project, dubbed the Integrated Ocean Drilling Program (IODP) Expedition 329, aimed to extract sediments from the abyssal plains of the SPG and investigate the microbial life that might reside in these barren depths. While one might imagine finding something extraordinary, the actual discovery was even more remarkable.

Section 1.2: A Find for the Ages

Morono and his team uncovered a community of microbes that may have remained in a state of suspended animation for over 100 million years. To put this in perspective, the oldest known hominid fossil is just over 4 million years old, while the extinction of the dinosaurs occurred 65 million years ago. The first flowering plants are believed to have evolved around the same time as these ancient microbes.

The researchers theorized that these microbes had been in a dormant state due to the lack of nutrients necessary for growth and division. Earlier studies indicated that while microbes were present throughout the depth of the ancient mud, they were found in sparse quantities—ranging from hundreds to millions of cells per cubic centimeter in these ancient sediments, compared to the tens of billions found in more nutrient-rich areas.

Chapter 2: Reviving the Ancient Microbes

This video showcases the astonishing discovery of 100-million-year-old microbes that scientists brought back to life, revealing the resilience of life forms.

The sediments housing these microbes contained vital nutrients such as dissolved oxygen, nitrates, phosphates, and dissolved inorganic carbon, albeit in minute quantities. Calculations indicated that the energy available for these microbes was exceedingly low. The presence of a dense, hard rock called porcellanite above the oldest sediments suggested that the cells had not migrated but had been trapped for eons.

Section 2.1: Testing Microbial Viability

To assess the condition of these microbes, Morono incubated them with stable isotope-labeled food. This experiment allowed the researchers to confirm that the microbes were alive and able to quickly revive, grow, and divide. Interestingly, fewer than 1% of the microbes formed spores—structures that allow some microorganisms to endure extreme conditions. Instead, the rapid response of the bacteria to nourishment indicated they were merely dormant.

This video explores the revival of 100-million-year-old microbes found beneath the ocean, showcasing their remarkable survival abilities.

Section 2.2: Implications for Life on Earth and Beyond

The implications of this discovery are profound. As descendants of bacteria-like cells, humans share a connection with these ancient organisms. In fact, the number of bacterial cells in and on our bodies far exceeds the number of human cells, and these microbes play a crucial role in our survival and identity. Their simple structure belies their complex functions, and the ability to survive in a dormant state for 100 million years exemplifies the incredible adaptability of life. Let us celebrate our microscopic companions!